On the holy night of Christmas in 1223, the quiet valley of Greccio became another Bethlehem. Francis of Assisi, with burning love for the Lord made flesh, desired to “make memory of that Child born in Bethlehem”, to see with his own eyes the humility of God lying in a manger, to make present again the mystery of God becoming man.

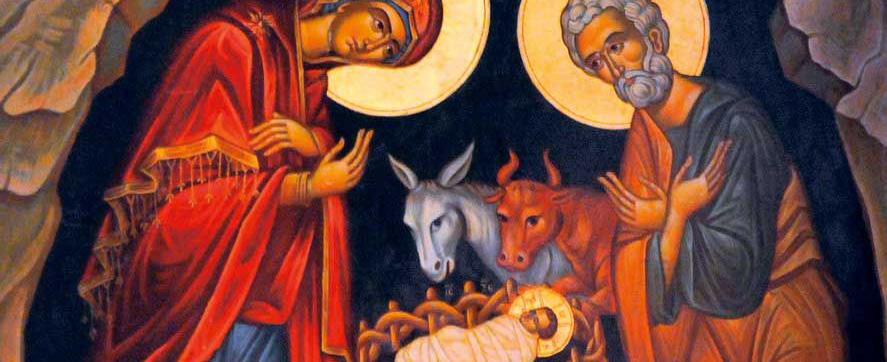

In a cave lit by torches and filled with song, Francis placed before the people a manger with hay, an ox and a donkey. There were no statues or decorations. He wanted everyone to feel the poverty and simplicity of that first Christmas night. It was an act of faith and of deep tenderness – a desire to make the invisible visible, to render present again the astonishing humility of God.

Upon the manger, he placed a portable altar for the Eucharist. There, the Child of Bethlehem was again laid before the people. There, the mystery of the Incarnation and the mystery of the Eucharist met. Through this holy night, Greccio became a new Bethlehem: heaven bent low, and God’s peace spread among those who came in faith and wonder.

The presence of the ox and the donkey, simple yet profound, holds a deep symbolic meaning. Though absent from the Gospel accounts, they appear in the prophecy of Isaiah: “The ox knows its owner, and the donkey its master’s crib; but Israel does not know, my people do not understand” (Isaiah 1:3).

From the earliest centuries, the Fathers of the Church saw in these two animals a prophetic sign. The ox, a beast of burden accustomed to the yoke, represents the people of Israel, who bore the law of God. The donkey, untamed and wandering, symbolises the Gentiles, who lived outside the covenant. Both come together at the manger, united around the Child who is the Saviour of all.

In that humble cave, the ox and the donkey are not mere decorations; they announce the mystery of reconciliation. As Paul writes, Christ “is our peace, who has made the two one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14). Before the manger, the walls that divide peoples, faiths, and hearts begin to crumble. Francis, who in 1219 had crossed battlelines to greet the Sultan with the peace of Christ, must have seen in these animals a living symbol of that same peace – a peace that unites Jew and Gentile, believer and unbeliever, reason and passion, earth and heaven.

The ox and donkey also speak of us. Before God’s mystery, we are often like them – slow to understand, stubborn, bound by instinct or routine. Yet in the presence of the Child, even the dull and unknowing awaken. Their eyes are opened; they recognise their Master. Thus, the manger at Greccio is not only a symbol of poverty but of illumination.

As Francis sang the Gospel that night – his voice trembling with tenderness, his tongue lingering on the sweetness of Jesus’ name – those who listened felt their hearts awaken. Thomas of Celano tells us that one of the faithful saw a child in the manger awakened from a “deep sleep” at the touch of the saint, adding “Thus Jesus was born again in the hearts of many who had forgotten Him.”

This is the miracle of Greccio. It is also the miracle of every Christmas.

Brothers and sisters, this Christmas, let the manger be our altar; let the Child be born in our hearts. Let the ox and the donkey – symbols of our blindness and hardness – recognise their Lord and bow before Him. Let us rediscover the tenderness of God who became small for our sake, for it is only by kneeling beside that humble manger that we find our peace, our joy, and our God.

0 Comments