St. Francis was born in the Umbrian city of Assisi about the year 1182. His parents were Pietro di Bernardone, a wealthy cloth merchant, and his French-born wife, Pica. Francis was one of the privileged young men of Assisi, attracted to adventure and frivolity as well as tales of romance. He passed his time among his friends, carousing and writing songs. When he was about twenty, he donned a knight’s armor and went off, filled with dreams of glory, to join a war with the neighboring city-state of Perugia. But the face of war-up close-was far from glorious. After surviving the carnage, and several additional months as a prisoner of war, he returned home, sick and broken. In the place of his previous gaiety he felt only a desperate emptiness, a feeling that there must be more to life than the success his parents envision him. He took to wandering the outskirts of town, where for the first time he noticed the poor and the sick and the squalor in which they lived. What he saw repulsed him.

Francis had always been a fastidious person, keenly alert to beauty and appalled by ugliness. But then one day, as he was out riding, he came upon a leper by the side of the road. The poor man’s face was horribly deformed, and he stank of disease. Nevertheless, Francis dismounted and, still careful to remain at arm’s length, offered him a few coins. Then, moved by some divine impulse, he bend down and kissed the poor man’s ravaged hands. It was a turning point. From that encounter Francis’s life began to take shape around an utterly new agenda, contrary to the values of his family and the world. In kissing the leper, he was not only dispensing with his fear of death and disease, but letting go of a whole identity based on status, security and worldly success.

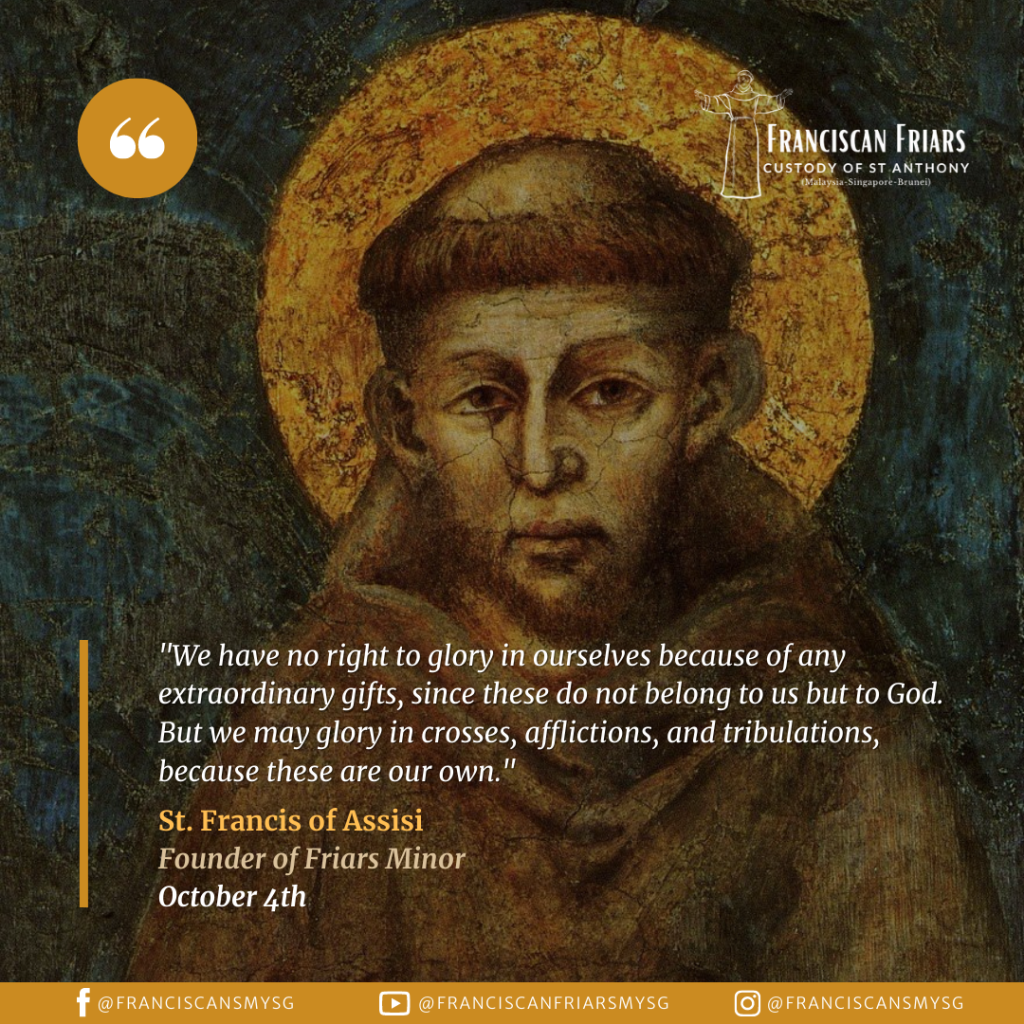

While praying before a crucifix in the dilapidated chapel of San Damiano, Francis heard the voice speak to him: “Francis, repair my church, which has fallen into disrepair, as you can see.” At first inclined to take this assignment literally, he set about physically restoring the ruined building. Only later did he understand his mission in a wider, more spiritual sense. His vocation was to recall the Church to the radical simplicity of the Gospel, to the spirit of poverty, and the image of Christ in his poor.

To pay for his program of church repair, Francis took to divesting his father’s warehouse. Pietro di Bernardone, understandably enraged, had his son arrested and brought to trial before the bishop in the public marketplace. Francis admitted his fault and restored his father’s money. And then, in an extraordinary gesture, he stripped off his rich garments and handed them also to his sorrowing father, saying, “Hitherto I have called you father on earth; but now I say, ‘Our Father, who art in heaven.'” The bishop hastily covered him with his own cloak, but the transformation was accomplished. Francis had become the Poverello, the little poor man.

The spectacle that Francis presented – the rich boy who now camped out in the open air, serving the sick, working with his hands, and bearing witness to the Gospel – attracted ridicule from the respectable citizens of Assisi. But, gradually, it held a subversive appeal. Before long a dozen other young men had joined him. Renouncing their property and their family ties, they flocked to Francis, becoming before long the nucleus of a new religious order, the Friars Minor.

The little community continued to grow. Francis and his companions lived outdoors or in primitive shelters. They worked alongside peasants in the fields in exchange for their daily bread. When there was no work, they begged or went hungry. Otherwise, they tended the sick, comforted the sorrowful, and preached the Gospel to those who would listen, an audience, in the case of Francis, that extended to flocks of birds as well as other creatures.

Francis left relatively few writings, but his life – literally the embodiment of his message – give rise to numerous legends and parables. Many of them reflect the joy and freedom that became hallmarks of his spirituality, along with his constant tendency to turn the values of the world on their head. Where others saw security, he only saw captivity; what for others represented success was for him a source of strife, an “obstacle to the love of God and one’s neighbor.” He esteemed Sister Poverty as his wife, “the fairest bride in the world.” He encouraged his brothers to welcome ridicule and persecution as a means of conforming to the folly of the cross. He taught that unmerited suffering borne patiently for love of Christ was the path to “perfect joy.”

But behind such “foolishness” Francis could not disguise the serious challenge he posed to the Church and the society of his time. Centuries before the expression became common in the Church, Francis represented a “preferential option for the poor.” Even in Francis’s lifetime, the Franciscans themselves were divided about how literally to accept his call to radical material poverty. In an age of crusades and other expressions of “sacred violence,” Francis also espoused a radical commitment to nonviolence. He rejected all violence as an offense against the Gospel commandment of love and a desecration of God’s image in all human beings.

Francis had a vivid sense of the sacramentality of creation. All things, whether living or inanimate, reflected their Creator’s love and were thus due reverence and wonder. In this spirit, he composed his famous “Canticle of the Creatures,” singing the praises of Brother Sun, Sister Moon, and even Sister Death. His gratefulness exceeded his powers of description. Addressing his Creator, he wrote: “You are love, charity; You are wisdom, You are humility, You are patience. You are beauty, You are meekness, You are security, You are inner peace. You are joy, You are our hope, and joy….Great and wonderful Lord, All-powerful God, Merciful Savior.”

Altogether his life and his relationship with the world – including animals, the elements, the poor and sick, women as well as men, princes, prelates and even sultan of Egypt, represented the breakthrough of a new model of human and cosmic community.

But ultimately, Francis attempted to do no more than to live out the teachings of Christ and the spirit of the Gospel. His identification with Christ was so intense that in 1224, while praying in his hermitage, he received the “stigmata,” the physical marks of Christ’s passion, on his hands and feet. His last years were marked at once by excruciating physical suffering and spiritual joy. “Welcome, Sister Death!” he exclaimed at last. At his request, he was laid naked on the bare ground. As the friars gathered around him, he gave each his blessing in turn:

I have done my part, may Christ teach you to do yours.

Francis died on October 3, 1226. He was canonized only two years later. His feast day is observed on October 4.

Source : The Franciscan Saints (Franciscan Media)

0 Comments